TEMPE, AZ—Providing a definitive explanation as to how and why early humans evolved away from their closest primate relatives, researchers at the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins presented findings Tuesday confirming that our species’ first ancestors began to climb down from trees to retrieve snacks they had dropped.

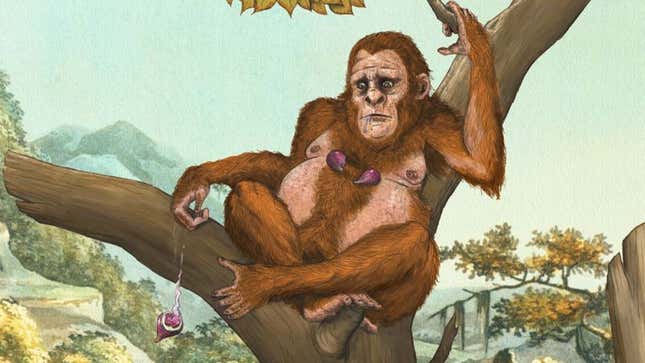

Anatomical evidence from the 6-million-year-old fossilized remains of Sahelanthropus peinaó—which was unearthed earlier this year in South Africa and is now believed to be the last common ancestor shared by chimpanzees and modern humans—suggests that the animal frequently descended from the jungle canopy to retrieve delicious morsels that it fumbled from its pudgy hands due to inattention, overeager eating, or a loosening grasp as it dozed off after a meal. According to scientists, it was this snack-retrieval instinct that gradually shaped the tree-dwelling hominid into the modern terrestrial Homo sapiens.

“For decades, we’ve speculated as to what caused our ancestors to evolve beyond their arboreal kin, and now we know for certain that it was all due to these proto-humans dropping snacks from their grease-covered fingers and then having to climb down out of the trees to get them back,” said anthropologist Gerald Dupuis, who noted that the fossilized specimen’s advanced tooth wear suggests repeated snacking on various salty and sweet treats, while its bone structure showed it to be significantly overweight. “We can say with confidence that nearly every subsequent adaptation in our species’ history was a product of our earliest relatives holding something appetizing to eat, accidentally letting go of it, and then having to will themselves to go pick it up.”

“No other evolutionary leap has had such a profound effect on humankind’s development,” he added.

According to Dupuis, everything humans have accomplished as a species—from “colonizing every corner of the planet, to building the Colosseum, to walking on the surface of the moon”—can be traced back to that first human forebear “sweating and breathing heavily as it struggled down a tree trunk” to recover a snack that it considered too tasty to let just lie there on the forest floor.

Before the emergence of the earliest humans, Dupuis said, if one of humankind’s primate ancestors had been spending a long afternoon snacking and a treat slipped from its hand, the animal was content to let it go and continue lying supine on a tree branch. However, he explained that at some point in the Miocene epoch, after dropping what scientists believe must have been a particularly delicious treat, one of the hominids realized that if it wished to continue snacking, it would have to come down from the tree, wander out onto the savanna, pick the morsel up, and put it back in its mouth—a behavior which, when first carried out, initiated the human lineage.

Dupuis stated that this desire to keep snacking was the impetus for several other key adaptations, including the increased brain size and cognitive capabilities that are the hallmarks of Homo sapiens. According to the anthropologist, once our early relatives realized they couldn’t reach their dropped snacks simply by extending their arms, they began gradually developing the ability to form abstract thoughts—including planning, problem-solving, projecting into the future, and evaluating alternative options—as they grasped the notion that if they did not retrieve the snack, they could not continue to experience its delicious taste.

Moreover, complex human emotions, from regret to longing to a desire for remediation, are also said to have begun emerging as humans began to reflect on the snacks they dropped.

“It is believed that the earliest rudiments of language also came about at this same moment in evolutionary history, with hominid vocalizations first beginning to carry meaning in terms of simple, crude complaints at having just lost one’s grip on a particularly desirable piece of food,” Dupuis said. “These irritated, monosyllabic howls gradually became more sophisticated, developing into a vocabulary used to more fully express frustration at having dropped a snack, and eventually as a means of requesting a little help from other primates on lower branches in grabbing the treats that had slipped from their hands.”

“Humans today still make grunts very similar to those of our first ancestors when we drop our own snacks,” Dupuis added.

The hominids’ final shift to becoming an exclusively ground-dwelling species is said to have occurred roughly 5 million years ago when, bloated and logy after having finished the snacks they had retrieved, they looked to the trees, realized what a hassle it would be to climb all the way back up there, and opted instead to take a nap on the ground.